ANTONIONI’S LEGACY FOR TRANSNATIONAL SPECTATORSHIP: FIVE AMBIGUOUS PIECES

A paper by Respondent Marsha Kinder, at the 2009 Society for Cinema & Media Studies (SCMS) Conference in Boston

Introduction:

Instead of responding to the other papers, I want to talk briefly about Antonioni’s legacy for film scholars and enthusiasts of my generation. This paper provides anecdotal accounts of five encounters with Antonioni over five decades and what they taught me about transnational spectatorship for his ambiguous open narratives. While his 1972 documentary on China, Chung Kuo/Cina, demonstrated the risks of ambiguity, a film misunderstood and harshly condemned by the Chinese government and not shown in that country until November 2004, my comments will focus on the value of this ambiguity.I. 1960, Seeing an Antonioni film for the first time.

It was his sixth feature L’avventura. Although many people walked out on this film at the Cannes Film Festival, those who stayed made sure it received the Special Jury Prize, for they realized the cinema had been changed forever! While some film historians now treat American spectatorship for European art films of that period as an exercise in bourgeois identification, for many American viewers in the early 1960s, it was transformative to see an ambiguous open-narrative depicting female subjectivity.

I was a 20-year old English major at UCLA at the time. It wasn’t merely a matter of liking L’avventura—I had seen other foreign films before—but it haunted me and ended up changing my life. For, it was so radically different that it made me switch from 18th century literature to film studies.

L’avventura , focuses on the subjectivity of a young woman played by Monica Vitti. Although we don’t know much about her (except her class), we can see she’s more alive and responsive than the bourgeois characters around her. We aren’t told these things; we have to perceive them on our own. In fact, most of the dialogue was banal—here, as in silent films, other formal choices were far more expressive:- the gestural language of the human body and face,

- the choreographed movements of the camera and characters,

- the spatial positioning of characters in the frame, especially in relationship to

- landscape and architecture,

- the subjective use of b&w (and later color),

- the focus on ambient sounds.

His characters are figures in the landscape, deeply embedded within a specific cultural and historical context. When my friends and I used to walk thru UCLA’s botanical gardens, we would imagine we were characters in an Antonioni movie.

Although his stories were told in the vernacular of melodrama, their minimal plots had gaping holes—questions were left dangling, there was no closure. They left room for us to project what was in our own minds. For, it wasn’t events that were so important, but rather the interior life of characters--their subjectivity--the way they perceive the world--what Pasolini later called “free indirect subjectivity,” Yet, Antonioni’s films showed how this subjectivity was shaped by and responded to social, political and historical change. By demanding active spectatorship, this combination helped prepare us for the post-structuralist synthesis and its politicizing of subjectivity.

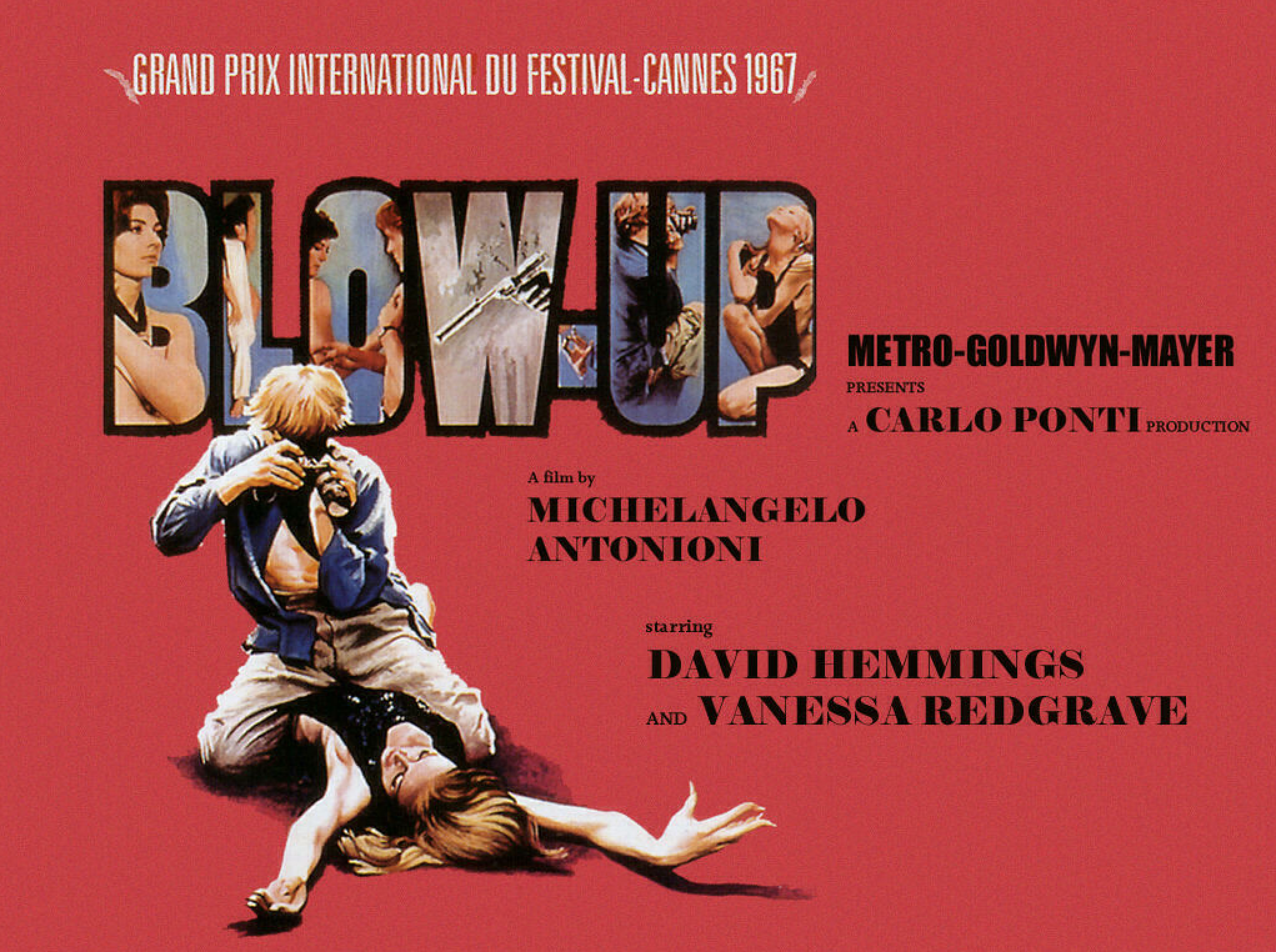

II. The second event occurred in 1967, when I published my first essay.

By then I was an assistant professor of Comp Lit at Occidental College. When I went to see Blow up, I was immediate struck by:

- the shift from a female to a male protagonist,

- the shift from interiority to material culture,

- the acceleration of pace,

- the figure 8 structure —where the second half mirrored the first half in reverse.

So when I came home from the movie theater, I stayed up all night writing an essay called “Antonioni in Transit,” which showed how Blow-up related to his earlier works. I sent it off the next day to Sight & Sound, and they published it in the spring 67 issue. Suddenly I was a transnational film critic! For me, this was a crucial transnational moment, for just as Antonioni had gone to England (to shoot swinging London), I purposely chose a British Journal to publish my first article, which was soon anthologized both in the US and in Italy.

A more immediate sign of its transnationalism was a fan letter I received from Maurice Yacowar, a Canadian who was then studying literature in England and

who assumed I must be living in London. His letter made me realize I belonged to this global community of fans who shared this passion for Antonioni

movies. We both moved to film studies!

The following year when I started therapy (remember, this was still the 60s), I gave a copy of this essay to my therapist, because it demonstrated changes in my own subjectivity. Antonioni’s films forced us to perform an active reading that revealed a great deal about our own interiority.

Download full essay on Blow-upIII. The third event occurred in 1968, when I met Antonioni for the first time.

Everyone knew he was shooting a new film in LA, and using USC as a location. Now that I was a published critic (and was teaching film courses at Oxy), I called MGM to set up an interview with him on location in Death Valley. There were two conditions. First, getting his approval after he read my essay on Blow Up. No problem--he especially liked my description of the figure 8 structure. Second, getting a commitment from Sight & Sound to publish it. Editor Penelope Houston agreed, despite her misgivings (since most of his interviews were the same).

But there were other problems. The young stars (Daria Halpern & Mark Frechette) had just been trashed by a visiting reporter from the NY Times, which made them suspicious of me. And the Assistant Director had just been injured by a stupid stunt performed by the stunt pilot, which made Antonioni worry that MGM might pull the plug. There were also conflicts between the Italian crew who were used to working with Antonioni and the Hollywood union crew members who were not. Still the conversation started out promising: for he asked me to collaborate on a book about the making of the film with Bruce Davidson photographs. Antonioni asked me to wait a few days, hang around the set, before doing the interview. Of course, I agreed.

But I was a critic, not a journalist—what could I say about a film I hadn’t seen? I had come to interview him. After finishing the essay, I sent him a draft of the interview to read over before it was published—in case I had made any mistakes, or if he wanted to change anything he said; a professional courtesy. Of course, it was VERY positive about Antonioni. Still, he freaked and tried to kill the article, but Penelope Houston loved it because it wasn’t like his other interviews and featured it on the cover. He over-reacted because he was afraid the studio wouldn’t like what he said. Of course, the book deal was no longer possible. He now said he didn’t want to be quoted—but then why agree to an interview? It didn’t make sense to me, but I felt I had failed him.

When I later wrote about the film (after I’d seen it) and when I was interviewed for a documentary on Zabriskie Point called In the Belly of the Beast, my comments were more favorable than most. Using widescreen and telephoto lens to create a sense of crowding—he clearly saw LA with foreign eyes and the results were fascinating.

ZP had many ties to Blow-up: seeing another culture through its figures in the landscape and the interplay between interiority and material culture through their different rhythms. Yet, I was disappointed by the banality of the language—perhaps that was less of a problem when seeing the earlier films in Italian with English subtitles. But wasn’t that combination of simple verbal language and complex visuals and audio-visual rhythms what made his films so powerful for transnational spectators.

Another

AMAZING incident soon made this vivid:

In 1969, on my first sabbatical, when I visited Aegina, a small Greek island, I complimented a young shop-keeper on his English. He told me he was learning

the language by reading English magazines and seeing movies. Then he went in the back to show me the magazine he was now reading. It was the Sight and Sound issue with my cover story on Antonioni.’s Zabriskie Point. When I told him I had written it, at first he didn’t believe

me, so I had to show him my passport. He was so amazed that he closed the shop and called his relatives in to come and meet me. As with Yacowar, we bonded

as transnational spectators and film fans.

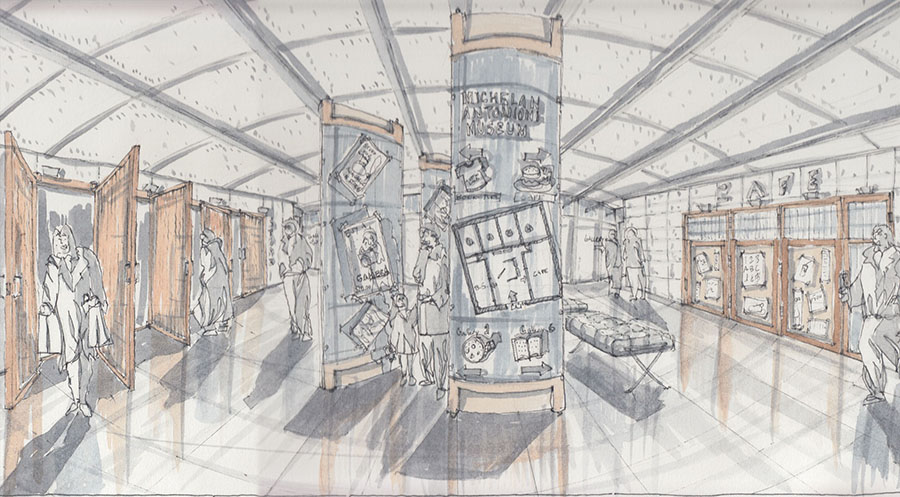

IV. The 4th event occurred 30 years later in 1998—

13 years after Antonioni’s stroke in 1985, which left him unable to walk or talk, and 3 years after the release of Beyond the Clouds (1995, co-directed with Wim Wenders), I made an abortive attempt to produce an interactive project on Antonioni’s work--in collaboration with Michelangelo and his wife Enrica and with his producer Stefan Tchaldchef. I wanted to explore Antonioni’s legacy for interactive database narrative, but instead I learned a lesson about transnational property rights.

In 1998, when Antonioni was in LA, he was no longer angry about my ZP essay (since the studio hadn’t read it) and he still remembered my piece on Blow Up. Tchaldchef told me about the collaborative dynamic with Wenders, who just lent his name so that they could get insurance, but who acknowledged it was Antonioni who had made all the directorial decisions for Beyond the Clouds (despite his stroke and his language impairment). Antonioni was trying to set his new movie, in the twin towers in downtown LA. He needed an American actress—a recognizable name, but couldn’t get any lead actress he liked to commit to the project. He had just been turned down by Robin Wright, who was told by her agent it would ruin her career. He couldn’t get past the Hollywood agents. It was a frustrating and humiliating experience for him.

We discussed the interactive project—which would show his legacy for open-ended database narrative. It was a collaboration with Charles Tashiro at USC’s

Annenberg Center, part of The Labyrinth Project & our Cine-disc Series of multilingual CD-ROMs on national and regional media cultures. Italian film

scholars Seymour Chatman and Luisa Rivi also were collaborating. Antonioni liked the idea.

We were making a virtual 3-D modernist museum that users could explore, like the actual Antonioni museum in Ferarra, with his water color

paintings and with stills from his films, which were used as visual icons for choosing movie excerpts, while “in the room the women come and go/Talking of

Michelangelo.” These figures in the interior landscape were avatars for his collaborators and critics.

We went to Ferrara, and Roma. We talked with Antonioni’s entourage, but finally had to abort the project because he had sold the rights to different people in each country. That made it impossible to get rights to use the excerpts. Now it might be different; but then it was a legal nightmare. In Rome, I met Vittorio Giacci, then director of the Rossellini Institute, who had made another interactive project on Antonioni (quite brilliant) that couldn’t be released for the same reason.

V. The final encounter occurred in 2007--a few months before his death, when Hollywood (the Academy) presented a final tribute to Antonioni.

Filling in for Chatman at the last minute, I was the moderator. I had a hostile encounter with Jack Nicholson over the unavailability of The Passenger for the past few years and his claim that he was “saving” the film from television spectatorship. He didn’t want to admit that he had held it back because he wasn’t happy with his own performance. He seemed to be drunk and babbled on, so that it was impossible for me or Antonioni’s wife Enrica to regain the floor. She and I were both angry and so was Antonioni. We wanted Antonioni to speak (but he couldn’t), and we wanted Nicholson to stop his rambling (which he didn’t). Whenever I spoke up, Nicholson attacked me (and the huge crowd was on his side)—I feared it would turn into another version of the coffee shop scene in Five Easy Pieces. Once again, I had failed Antonioni.

But, despite this encounter with Nicholson, that night was an historic event. It was the premiere of a new version of his 1975 film, THE PASSENGER, which was

soon released by Sony Pictures Classics –a restoration of the director’s cut, which had not previously been shown in the US.

In THE PASSENGER, Nicholson plays a reporter, covering a story on guerilla warfare in North Africa, who impulsively trades identities with

a deadman so that he can escape the complications of his own life. He doesn’t anticipate what complications the new identity will bring. There’s a

wonderful scene where the reporter is interviewing an African and they suddenly switch roles—with the African taking the camera and pointing it at the

reporter. As spectators, we are also constantly being asked in this film to switch our own position. And as we viewed it that night (in 2007), in a far

different historical context, one in which our attitudes toward guerilla warfare were probably very different from what they were in 1975, we were even

more aware of the way his films capture these changes in our own subjectivity.

That night we also saw a brief excerpt (the last 4 minutes) from Antonioni’s final documentary, made in 2004 --with the assistance of his wife Enrica and

documentary filmmaker (and longtime friend) Carlo Di Carlo—a film called MICHELANGELO LO SGUARDO (and in English, MICHELANGELO, EYE TO EYE, or THE GAZE OF MICHELANGELO). The film opens with two written

statements:

In 1985 Antonioni suffered a stroke and was confined to a wheelchair.

In 2004, through the miracle of cinema, he made this visit to San Pietro in Vincoli.

This is what I said about the film that night:

,

Despite his confinement in a wheelchair, Antonioni used the magic of his own cinematic artistry to walk into the room, touch the flesh and return the gaze

of Michelangelo and his Moses. Antonioni couldn’t walk or talk, but he could see and hear, and he could touch and feel, and, above all, he could still

direct. Without saying a word, he could still use cinema to convey subjectivity--his own way of encountering the worlds of materiality and spirit. This was

always the unique achievement and primary legacy of his cinema.