- Co-author of :

- 2 unproduced screenplays: Tristram Shandy (1970) & Mary Wollstonecraft (1976)

- 2 books: Close-up: A Critical Perspective on Film (1972) & Self and Cinema (1980)

- 13 critical essays on film:

- "Rosemary's Baby," Sight & Sound (Spring 1969)

- "Odd Couples: Woman and Manchild in Harold and Maude, Minnie and Moscowitz, and Murmur of the Heart," Woman & Film 11 (1972).

- "Woman and Manchild in the Land of Broken Promise," Women & Film III- IV (1973).

- "American Graffiti," Film Heritage (Winter 1973).

- "Bertolucci and the Dance of Danger: Last Tango in Paris," Sight & Sound (Fall 1973). Reprinted in Sight and Sound Reader (British Film Institute, 1982).

- "Truffaut's Gorgeous Killers," Film Quarterly (Winter 1973).

- "Seeing Is Believing: The Exorcist & Don't Look Now," Cinema (1974). Reprinted in American Horrors, ed. G.A. Waller (University of Illinois Press, 1987).

- "Madwomen in the Movies," Film Heritage (Winter 1974).

- "The Night Porter as Daydream," Literature/Film Quarterly (Fall 1975).

- "Adaptation as Criticism: Tristram Shandy on Film," Eighteenth Century Studies (Spring 1977).

- "Insiders and Outsiders in the Films of Nicolas Roeg," QRFS (Summer 1978).

- "Sexual Politics in Sweet Movie," QRFS (Fall 1978).

- "The Losey Pinter Collaboration," Film Quarterly (Fall 1978).

Besides being best friends and colleagues at USC, we wrote many works together, including an essay on collaboration. We used to take turns at the typewriter—one of us would type while the other paced back and forth talking. I was always good at creating the overall structure, and she was much better at choosing the precise words. But over the years we each absorbed the strengths of the other, so we both emerged as better writers. When she died in 1988, I gave a tribute at her Memorial Event at USC, which was published in Cinema Journal (Fall 1988).

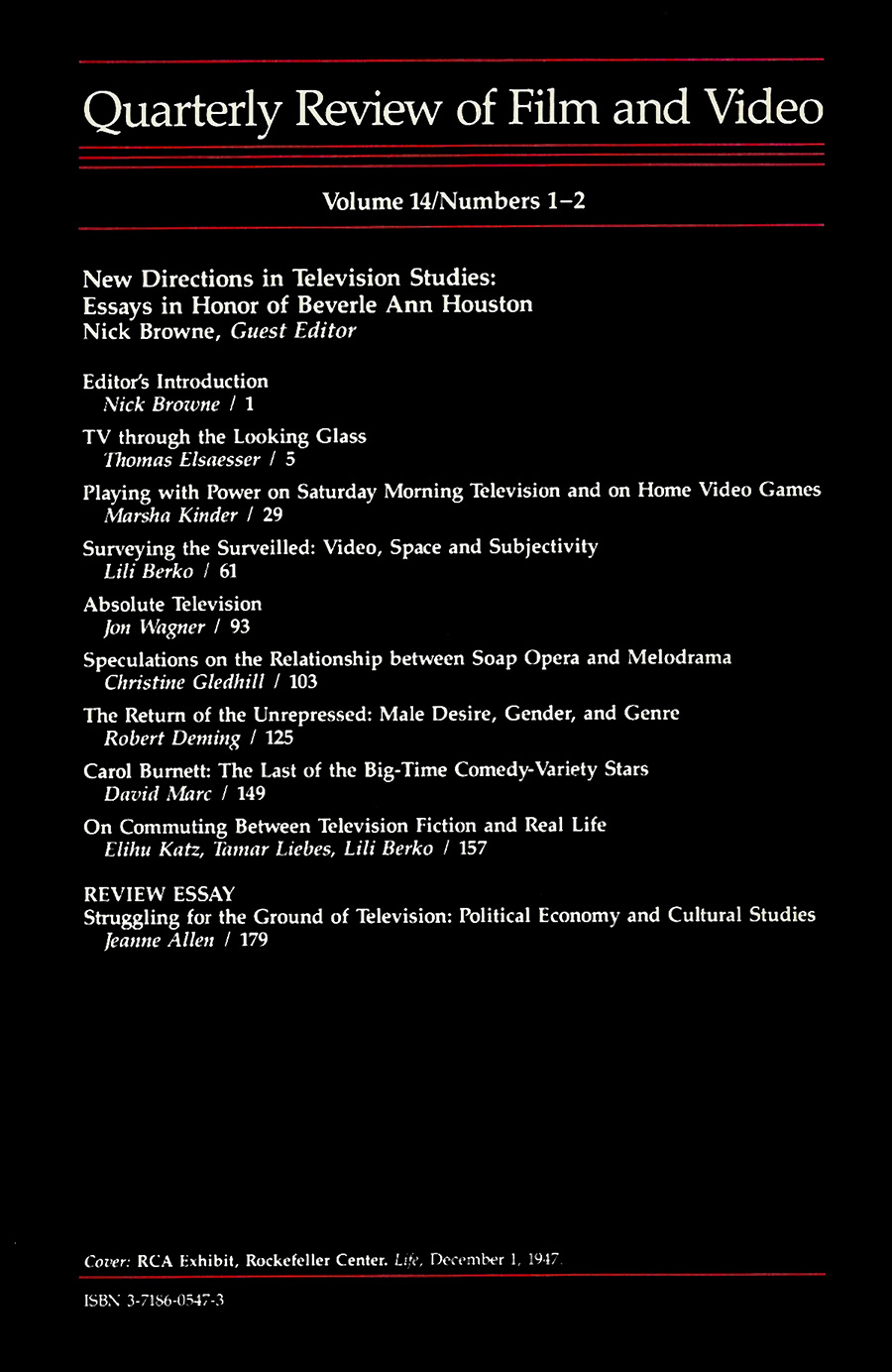

Beverle also collaborated with others, including filmmaker Chick Strand, who captured her vitality in a brilliant sequence from her 1980 film, Soft Fiction. In the early 1980s, Beverle was one of the first American film scholars (along with Nick Browne and Bob Rosen at UCLA) to make an official visit to China, where she gave a series of lectures that launched a transnational conversation on melodrama. In 1992, Browne dedicated a special issue of QRFV to Beverle, titled, "New Directions in Television Studies" 1:2 (1992).

BEVERLE ANN HOUSTON (1935-1988)

A Tribute by Marsha Kinder read at a Memorial Event on May 4, 1988 at the USC School of Cinema-Television, for the Dedication of the Beverle Houston Critical Studies Seminar Room and the establishment of the Beverle Houston Scholarship Fund. An edited version of this tribute was published in Cinema Journal (Fall 1988).

Beverle Ann Schwartzman was born in West Reading, Pennsylvania on December 23, 1935, and grew up in Philadelphia. When her parents separated, Beverle and her mother Jeanne moved in with her aunt and uncle and their two children Bede and Joey. So she grew up in an extended family, which was a very important fact in Beverle’s life. She was never very rebellious against her family: she always felt a strong solidarity with them. She expected women to be strong and independent like her mother and aunt, whether single or married. And that experience helped Beverle’s feminism come more naturally to her.

When Beverle was in the fourth grade, her teacher informed the class that children from broken homes are unhappy and should be pitied. Beverle immediately stood up and told the teacher that was not true—that her parents were divorced and yet she was still a happy child living in a happy home and certainly didn’t need to be pitied. Beverle was sent to the principal’s office for being rude and for contradicting the teacher, but she immediately became a mythic figure for her classmates. What this story so vividly reveals about Beverle is not only her moral courage and indomitable spirit, but also her fierce loyalty to her mother and to the rest of her extended family. And also an absolute confidence in her own emotional reality.

Though Beverle had many remarkable strengths—physical, intellectual, spiritual and verbal—it was her emotional honesty that was perhaps the most remarkable of all. When you were with Beverle , you were always confronted with her emotional honesty, which forced you to be more honest yourself—whether you were a relative, a friend, a husband, a lover, a student, a colleague, an acquaintance, a committee, or an institution. And that made you feel more like extended family.

For Beverle, being raised in an extended family could never be a handicap; she saw it as desirable. She used to fantasize that some day she and all of her close friends would retire and live together in one big happy family. Although she may not have lived long enough to fulfill that fantasy, all through her life she was drawn toward extended families and helped to create them around her.

While Beverle was an undergraduate at the University of Texas (a double major n English and Journalism), she decided to get a summer job at Grossingers, the most well known resort hotel in the Catskills. Not only did she demonstrate her extraordinary intelligence and dazzling administrative abilities by quickly being promoted to a position at the front desk, but she also won the heart of one of the Grossinger heirs. They were married at the resort and had room service ever after, and she became a member of one of the most legendary extended families in America. Although such a fairy tale marriage might be the dream of many a Jewish American Princess, for Beverle it soon turned into Rapunzel. She walked away from the marriage and the money and went to Graduate School at the University of Pennsylvania where she would get her M.A. in English literature and where she would meet her second husband, David Houston.

David was the total antithesis of the Grossingers—very blond and Anglo-Saxon, a Marxist economics professor who refused to own property but who also saw himself as a Hemingway hero. They toured through Europe on a motor bike and then came to UCLA where David had a new job and Beverle entered the doctoral program in English literature. It was 1962, and that’s when Beverle and I became friends.

What immediately struck me about Beverle was how much fun it was to be with her, no matter what you were doing. What a great sense of humor she had, what a capacity for combining shrewdness, wit, idealism, and pleasure. She loved to dance, party, sing, ride horses, cook, and she especially loved to eat and to talk.

Beverle took a sensual pleasure in using words with precision, playfulness and passion—in feeling them roll off her tongue, in hearing their rhythms, and in seeing them take shape on a page. Everyone who knew her has absorbed many of her wonderful expressions. We can hear her voice in our own speech. It winds through our hearts and minds like a bright-colored ribbon. The pleasure that she took in language was part of her extraordinary capacity to relish life in all of its lushnessfrom the most mundane creature comforts to the most esoteric abstractions.

Together with Rosalie Newell, Beverle and I formed another extended family at UCLA—like the proverbial three sisters, all studying 18th century English literature under Ralph Cohen, whom we considered the most brilliant professor at the university and who became our intellectual father. Our husbands and our fellow students used to tease us, calling us the formidable female troika as we marched through the halls of the humanities building three abreast; others called us the Marx sisters. But we felt a great sense of solidarity—in helping each other survive the traumatic jolts of the 60s and in helping each other get our degrees and divorces.

Beverle’s dissertation was on Jonathan Swift’s Tale of a Tub and Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, a project that helped to develop her exquisite sense of irony. Her first academic job was in the English Department at Cal State/Northridge, where she proved to be a wonderful, charismatic teacher. In 1968 she was one of the few professors arrested along with students at a political demonstration on behalf o minority rights and, as a consequence, she lost her job and became a cause célèbre.

That year there were no openings in 18th century English literature at the local colleges, so Beverle took a job teaching at Oakwood, a private high school in the valley, and the kids were crazy about her. She became totally involved in the life of the school and made a number of lifelong friendships both with her students and their parents. When she returned to college teaching, Oakwood made her a member of their Board of Trustees.

Though she was offered a good job in Canada, Beverle decided to stay in LA, not only because she didn’t want to leave her extended family of friends, but also because LA was her favorite city in the world, the capital of post-moderenism. So in 1970 she took a job at Pitzer College, where again she was enormously successful as a teacher and as a leader of the faculty.

It was right around this period that Beverle and I wee collaborating on our first book, Close-Up. We started writing together back in 1968. One night we went to see Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby and both loved it. Then we went to her house for a cup of tea, continuing our heated discussion about what made the film so fascinating. I suggested we write an essay, so we stayed up all night writing, each taking a turn at the typewriter and the other talking away. And when the morning came, the essay was done ad we sent it off to Sight and Sound where it was published. Together we wrote two books, two screenplays (one on Tristram Shandy and the other on Mary Wolstonecraft), and 13 articles. And the writing was always enormously enjoyable because there was constant feedback and always lots of laughs. We each absorbed part of the other’s style. Beverle was wonderful at choosing precisely the right word or phrase to describe the textures of the image, and I was always obsessed with structure. Even now when I’m writing alone, I sometimes write a sentence that sounds just like Beverle. We both internalized the voice of the other. That’s what happens when you write with someone for ten years.

The last stage of our collaboration was here at USC, in helping to make our Critical Studies Program one of the best in the country. When Beverle applied for the position of Director of Critical Studies, she gave a dazzling presentation called “An Old New Critic Looks at the New Discourse.” It was not only brilliant, but also accessible and funny. It honestly reflected her own experience of having been trained as a humanist in a discourse that prized geniuses and masterpieces, and then having taught herself a new set of theoretical ideas that erased the boundaries between high art and pop culture. These ideas weren’t merely abstract concepts for Beverle; they deeply affected her life. They helped her decide to leave Pitzer, to change her primary academic field from literature to film and then to television, to leave her old triumphs behind and to take on new risks. These changes cost Beverle a great deal. She internalized these struggles and even got pneumonia. But they also enabled her to get the job at USC.

Beverle did an extraordinary job as the Director of Critical Studies—as one who demonstrated remarkable abilities as an administrator, who could see the large picture and still attend to the finest details, who had unique intuitive abilities in assessing character and in successfully dealing with a wide range of people, who could make and implement executive decisions while still making us all feel like valued members of an extended family, who immediately elevated the stature of our program not only within our own School of Cinema-Television, but also within the University at large and within the international field of film and television studies. She knew how to use power; she didn’t fear or abuse it.

And while she was devoting all of this energy to administration, she was also making tremendous personal growth as a scholar, in writing her very best work: on the power baby at the center of films by Orson Welles, on Dorothy Arzner’s unique methods of subversion, on the metapsychology of television as a medium of endless consumption, on the interaction between television and cinema in defining different spectator positions and different kinds of pleasure. All of these essays drew on and were tested against her own lived experience as an oral personality, as an ardent admirer of melodrama, and as an obsessive consumer of television. They proved to be tremendously influential in the field.

During this same period she also became the co-editor of Quarterly Review of Film Studies and helped it to become the best theoretical film journal in the country, generously giving her time to edit the work of other scholars. Beverle was a brilliant editor, a talent which was first demonstrated to the world in her special issue on Feminist Theory, which she guest-edited for QRFS in 1978 and which became one of the journals most influential volumes. I remember in particular how closely she worked with Christine Gledhill on her historic essay, “Recent Developments in Feminist Criticism.” And Christine will never forget it either—that’s one of the reasons why she has dedicated her latest book on melodrama to Beverle.

During this same period, Beverle was also giving papers at international conferences in London and Urbino, and in the summer of 1984 she was one of the first American film scholars to be invited by the Association of Chinese Film Artists to lecture in China and to have her lectures published in Chinese. She was deeply moved by the Chinese people, by their collective idealism, partly because it appealed so directly to her own feelings about extended family. A wonderful letter from two of her Chinese students, Bao Yuheng and Chen Xihe, clearly demonstrates that she was able to communicate these feelings across the barriers of language and culture. She became their “dear Dr. Beverle,” whom they saw as one of the first Americans to encourage their young artists and, as Nick Browne has observed, the first to use the study of melodrama as a means of strengthening the emotional bond between the two cultures.

While Beverle was performing these administrative and scholarly feats at home and abroad, she was also continuing to excel in the classroom here at USC—in developing experimental new courses, in recruiting and supervising some of the best graduate students we have ever had in critical studies, and also in encouraging and supporting some of the most talented students in production.

In all of these ways, Beverle made a tremendous contribution to our School of Cinema-Television and to our field—generously devoting her time, energy, passion and intelligence to this increasingly large extended family. And yet, amazingly, this extraordinary period of accomplishment lasted only four years, from 1982-1986. Beverle felt that these four years as Director of Critical Studies at USC brought her something of great importance in return. She used to tell me that for the first time in her life, she felt she was in a position that demanded her full strength, that enabled her to draw on her full powers. And that was truly exhilarating to Beverle Ann Houston, our “dear Dr. Beverle” who, as the Chinese say, will always share in our victories and always live in our hearts.