In the late 1970s, Kenneth J. Atchity and I decided to start a new interdisciplinary journal on dreams and their relation to the waking arts. Although we were both teaching at Occidental College in the Department of English and Comparative Literature, we had much broader interests that included—music, painting, sculpture, architecture, performance, and film. Together we composed a letter describing the journal and inviting artists to contribute a brief article describing how they used dreams in their own artistic practice, with concrete examples. We were interested in going beyond a codified dream style like surrealism and exploring a much broader set of relations across the arts.

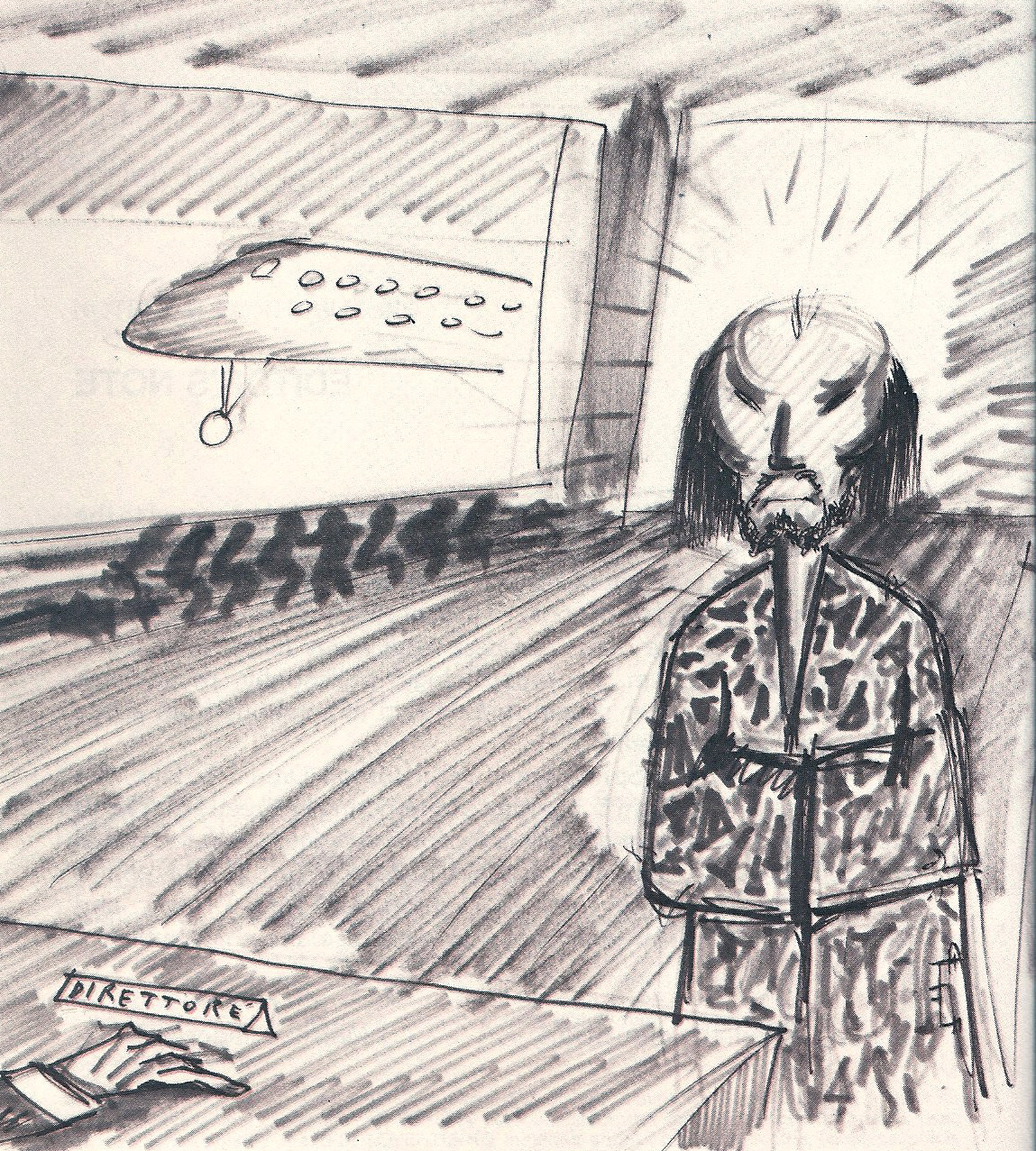

Much to our astonishment we immediately received dream reports from an impressive array of filmmakers (including Federico Fellini, Orson Welles, Stan Brakhage, Dusan Makavejev, Paul Sharits, Ed Emshwiller, Pat O’Neill, Chick Strand, Bruce Connor), novelists (John Rechy, John Fowles, Ursula K. LeGuin, D.M. Thomas, William Burroughs, Paul Bowles, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Joyce Carol Oates,), and poets (Denise Levertov, W.S. Merwin, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Howard Nemerov, Gary Snyder)—just to name a few. We quickly assembled an impressive Advisory Board, which included not only artists like John Cage and many others listed above, but also critics, literary scholars, psychologists, anthropologists, and scientists, many of whom contributed ground-breaking essays. Our board also included dream experts like George Devereux and Ann Faraday and two of our nation’s leading neuroscientists working on dreams—William Dement of Stanford’s Sleep Research Center and J. Allan Hobson of Harvard Medical School.

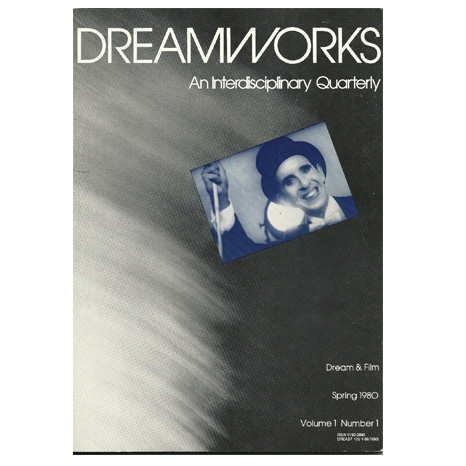

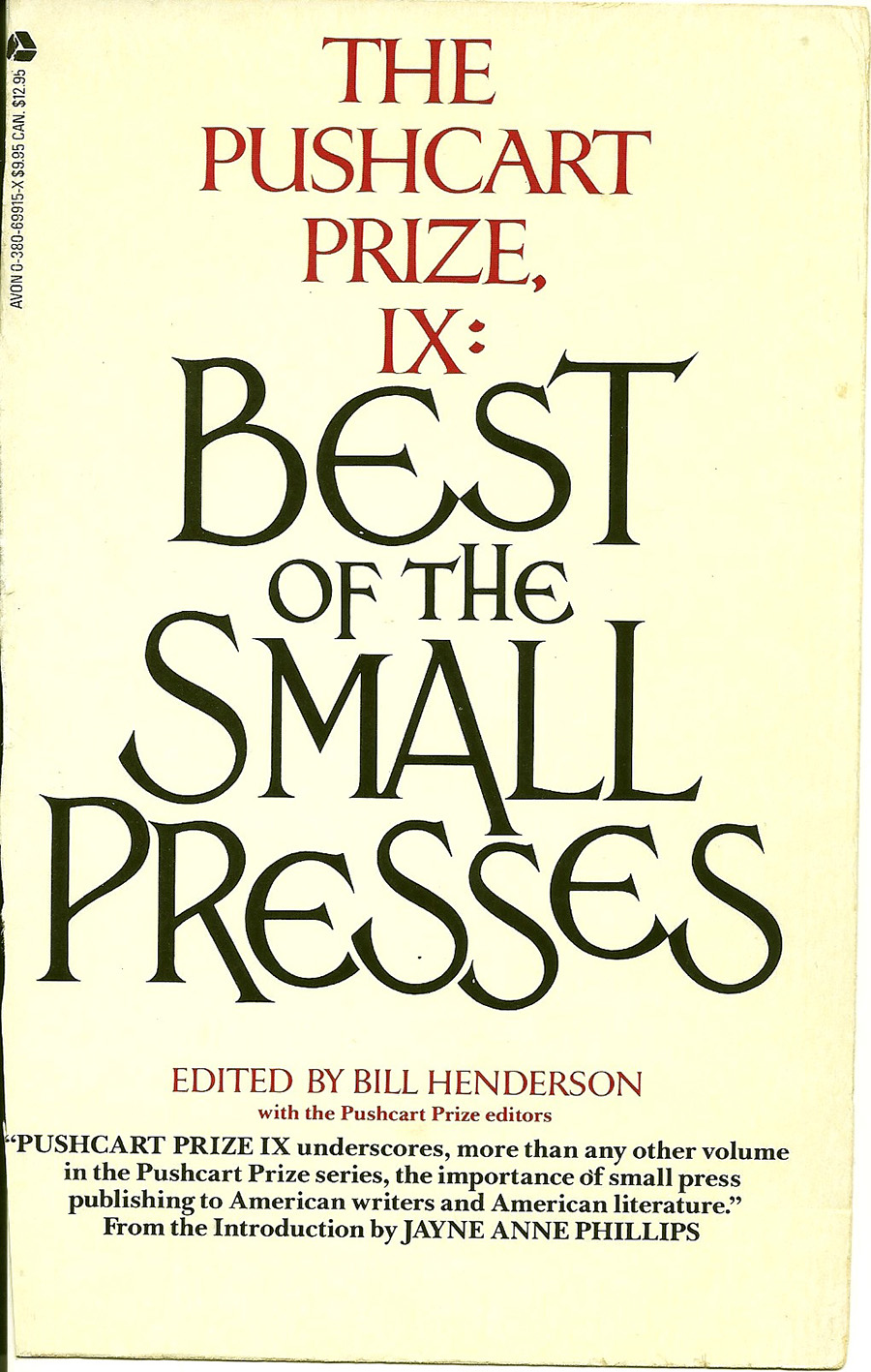

As co-editors, we took turns editing the journal. I edited our first issue, which appeared in Spring 1980 with the focus on Dream & Film, and Kenneth edited the second, on Dream & Poetry. Our journal soon won a Pushcart Prize, an American award that honors the best "poetry, short fiction, essays or literary whatnot" published in the small presses over the previous year. The journal continued for nine years, ending in 1988 with a final issue on Dreams & Adaptations. By then I was a film scholar at USC and we had both moved on to other fields.

We called the journal DREAMWORKS, to put the emphasis on concrete works and to evoke Freud’s dreamwork theory, which helped explain the productive relations between dreams and the waking arts. Yet, we never trademarked the title, which meant there was nothing we could do when a new Hollywood studio later appropriated the name. They stole it from us, but we had also taken it from Freud. So we called the on-line version DREAMWAVES.

drawing sent by Fellini

winner of the Pushcart award