When I decided Labyrinth would produce new works, the first person I thought of as a collaborator was Pat O’Neill, the ultimate creator of non-linear films, whose multi-layered narratives from the 1970s moved not only horizontally and vertically but also in and out of depth. What I admired most was the layered quality of the images, their sensory beauty, and surrealist wit, a combination that made them emotionally compelling no matter how abstract the content might be.

As it turned out, Pat was soon starting a new film on the Hotel Ambassador and was eager to collaborate with us on the project. But we would have to wait until he was ready. We knew he was uncompromising and that he sometimes devoted ten years to a project, but we all felt it was a privilege to work with him so were willing to wait. In the meantime, we focused on the setting—the historic hotel where Bobby Kennedy was assassinated, where the jury for the Charles Manson trial was housed, and where Nikita Khrushchev stayed during his infamous visit to Los Angeles. It was a repository of traumatic historical memories waiting to be destroyed. No longer open, it was then being used as a set in noir movies like Barton Fink. According to California historian Kevin Starr, it was the first-class hotel that proved Los Angeles was ready to be a first-class city—a midtown location where the downtown power-brokers mingled with the Hollywood stars. Like all hotels it combined public and private space—world famous arenas like the Cocoanut Grove nightclub where stars played and performed and the Ambassador room where Kennedy gave his final campaign speech, versus those private rooms where successive waves of occupants lived out their personal dramas. It was this unique Los Angeles setting that launched Labyrinth’s new genre—the postmodernist city symphony.

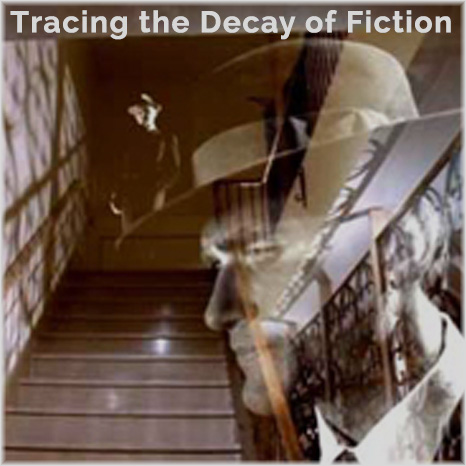

Once Pat’s film was in production, we had 35 mm footage of the rooms with ghost-like figures gracefully gliding through them. Visitors navigated the camera moves, moving magisterially from one space to another, deciding whether to call forth the ghosts or seek out hot-spots that gave access to other dramas. But the assassination and its aftermath were always lurking, whether you chose the documentary footage or an historical reconstruction. You could always visit the archive in the basement and use the original architectural plans to go directly to a specific space, or move outside the building to visit the Miracle Mile and its recent urban developments. These areas are not present in Pat’s movie. Nor is the earthquake, Pat’s favorite feature of the DVD-ROM, which triggers a sequence of random sounds and images, reminding you of what you have not yet seen or heard. The layering of sound was as rich as the image—the combined work of Pat and his soundman George Lockwood, our own brilliant assistant Adam King, and Walter Murch as consultant. There was only one rule to follow: avoid sound/image synchronicity at all costs.

At the Future Cinema exhibition at ZKM, the project had two adjacent rooms—one for the film, the other for the DVD-ROM, which were both open-ended. Neither explained the other but both were totally intriguing.